By: Alix Rosseau | Staff Writer

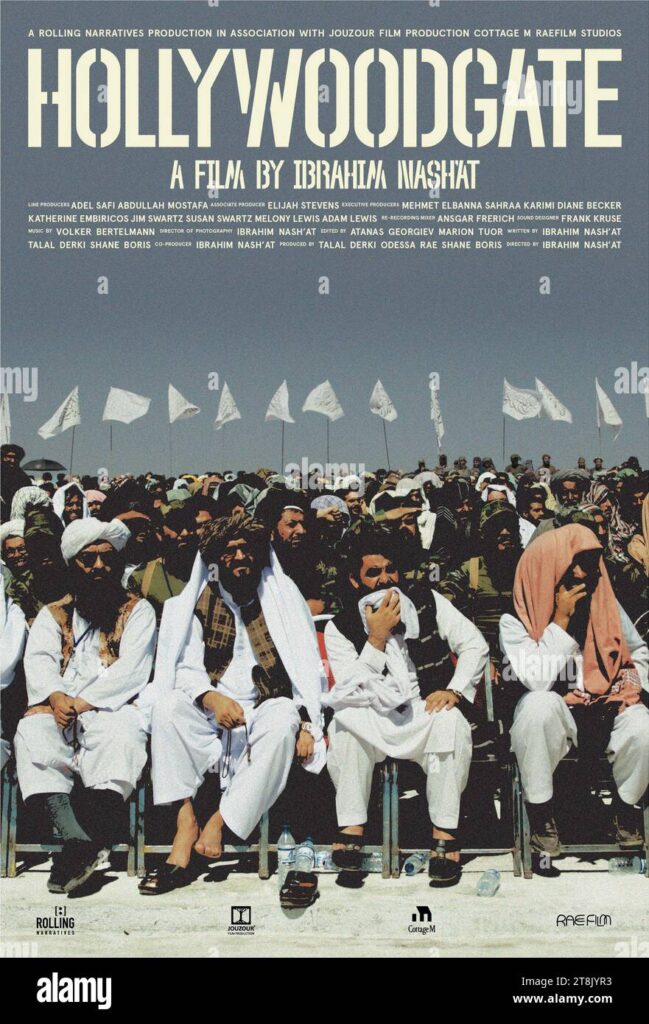

London, United Kingdom – As giddy journalists and immigrants pile into an intimate screening room in a secluded annex of central London, many have come to watch Hollywoodgate—a documentary by Ibrahim Nash’at that follows Taliban officials and their quest to rebuild their country in a post-American occupation world. The film does not shy away from showing the realities of the country’s dire healthcare system, women’s rights and the Taliban’s viewpoint on America’s troops’ two decades-long stay.

Located in Paddington, The Frontline Club was founded by British cameraman Vaughan Smith in 2003 after reporting on America’s invasion of Iraq that same year. Today, The Club has welcomed some of the world’s most known journalists, filmmakers, and thinkers worldwide. In the case of this screening, many journalists from the BBC, CNN and The Times newsrooms watch this film, making small talk over pints and reminiscing some of the previous assignments that have taken them to countries such as Syria, Iraq or Taiwan.

Like many journalists, Nash’at arrived in Kabul just a few months after the Biden administration pulled out American troops from Afghanistan. At the time, the Taliban were looking to portray a particular narrative to the West and carefully selected which journalists would have access to their headquarters. Nash’at asked for a year-long permit to gain access to the Taliban’s top officials, the infamous warlords were quite surprised.

“It’s a system of favoritism,” he tells the audience.

He was often subject to six-to-seven-hour long interrogations and would go days with his camera confiscated. A tactic that many regimes still use to this day as a method of intimidation towards the press operating in war-torn and corrupt countries.

Often shooting at the back of American troops’ leftover trucks or when visiting former American military bases, he was advised by his producers to shoot Taliban military officials “from below” to stretch his access to military bases and the Taliban headquarters. This repetitive and psychologically taxing process would often leave Nash’at and his translator having to reach out to new locals to continue shooting, gaining over one 150 hours of footage solely on one trip.

After a year of being embedded with the Taliban, Nash’at partially jokes that he left with footage and a case of Stockholm Syndrome, an aspect that many conflict journalists and filmmakers experience witnessing the brutal impacts of armed conflict for an extended period.

Odessa Rae, the Canadian-American producer of HBO’s Navalny, she was impressed by Nash’at’s abundance of access.

“When I signed on, the documentary was already in production, so I ended up paying for Ibrahim’s trip to go back home and additional funds for him to continue shooting in Afghanistan.”

The film, which premiered and won the “Best Documentary” category at the 80th Venice International Film Festival, instigated a lot of conversation among countless governmental bodies since its original screening in 2023. Among the governmental bodies who have decided to screen the film include the US Embassy in Doha, Katar, the European Parliament and UNESCO in 2025.

In the case of the November 26th screening, bursts of laughter were not uncommon, and both Nash’at and Rae agreed that this audience of journalists understood the dark humor that comes with shooting in war zones.

“They can come to work if they hide their face,” one Taliban official tells the camera.

Another joke is that he would much rather have his wife stay at home to take care of his children than go back to work as a general practitioner. This aspect is still lacking in Afghanistan’s healthcare system, and Nash’at later emphasizes it during the Q&A.

“At one of the [recent] screenings, I was told this documentary was a Taliban version of The Office,” Nash’at said.

Though the small team understands that not all audiences will understand the dark humor in this film, they hope that audiences walk away with an understanding of the future of America’s foreign policy.

When asked about how Hollywoodgate can build bridges and provide lessons for future generations from this two-decade-long occupation, both Nash’at and Rae shared words of wisdom.

“Whenever the next time a presidential administration decides to go to war with another country, the future generations can understand the impact of these future occupations and if they are essentially necessary for the good of the citizens whose country is being occupied.” said Nash’at.

“I hope that it builds bridges more than anything and that it helps us understand the future of American foreign policy,” adds Rae.

There has also been a consensus by nonprofits, governments and public officials that Afghanistan’s state today relates to the complex history it has endured for countless years.

“Afghanistan is no better off today than it was twenty years ago,” states Odessa Rae.

Photos provided by Alix Rosseau and Hollywoodgate.