By Lily Margaret Jones | Co-Editor-in-Chief

On November 30th, the first floor of McKillop Library was host to a panel discussion titled “Baby Hairs and Afros: How Race and Gender Intertwine.” The panel was organized by three students as an assignment for their introductory Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies class, taught by Dr. Donna Harrington-Lueker.

The assignment asked students to choose from a list of topics and host a community event that would help to “shed light” on that subject. Two other groups of students chose to do panels, which took place earlier in November; one focused on gender and the LGBTQA+ community, the other on women, consent, and sexual assault.

Students Regan Sealy ’18, Jessi McNeil ’18, and Emilee Duffy ’17 chose to do a panel on the topic of intersectionality, a term coined by theorist Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, meaning “the way social classifications like race, gender, religion, and class are interconnected.”

The three decided to name the discussion “Baby Hairs and Afros” in reference to the song “Formation” off of Beyoncé’s latest album, which focuses both on her race and her role as a woman.

“Beyonce’s album Lemonade has a reoccurring theme of intersectionality,” Regan Sealy said. “Everyone knows who Beyoncé is, so we thought it made a good connection.”

As part of their assignment, Sealy, McNeil, and Duffy had to find speakers for their panel, contact them and confirm their spots, make a list of questions to incite thoughtful discussion, and create any necessary materials, such as promotional content for the event.

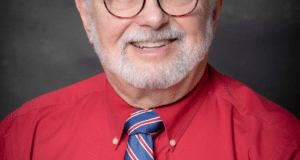

They chose three women of color to sit on their panel. This included Wilmaris Soto ’16, a Salve Regina alumna, founding member of student organizations the Black Student Union and the Sisterhood, and social worker; Dr. Juanita Ashby Bey, an assistant professor of Education at Salve Regina who has researched the impacts that institutional racism has on the educational experiences of African American and other minority students; and Dr. Julia Jordan-Zachery, award-winning scholarly writer, professor of Public and Community service, and director of the Black Studies Program at Providence College.

Sealy said that each woman was chosen for a different and valuable point of view based on her own professional and personal experiences.

When asked a question about African American women and public policy, her area of expertise, Dr. Jordan-Zachery said that historically, public policies have “failed black women and women of color in general.”

“Why is it that the quote unquote ‘gender gap’ in voting has come on the backs of minoritized women, racially minoritized women, why is it that they remain invisible?” she posed. “We’ve stopped talking about black women in public policy when there was welfare reform back in 1996. We don’t talk about black women. We don’t talk about Latina [women.] We don’t talk about Asian women, we don’t talk about native women.”

Dr. Jordan-Zachery also pointed out that the invisibility of women of color, particularly black women, goes beyond the political and into the social realm. Dr. Ashby echoed these sentiments in her response to a question about how intersectionality is seen in social interaction, specifically with leadership.

“As an African American woman who has held leadership positions, and I have many friends who are African American and hold leadership positions, the response to African American women as leaders is very aggressive,” she said. “It’s like the system is not designed to work with us, it’s designed so that we really do have to demonstrate over and over again our ability and our effectiveness and that we understand where we’re going and what the institution needs. So that was one of the most shocking experiences I’ve seen as an African American professional leader.”

Dr. Ashby Bey said that addressing this reality and speaking up not just once, but always, is the potential key to breaking down oppressive hierarchies.

“When you are privileged, and I’ll say when you’re a white woman, or a white male, you don’t have to think about a lot of stuff that women of color have to think about,” Wilmaris Soto agreed. “In terms of having to fight harder to be recognized in this society, it’s something I think about all the time. Just getting into the workforce especially, I feel like I definitely have to fight a lot harder and work a lot harder to be looked at with respect.”

For Sealy, the panel assignment served to be a worthwhile learning experience, and she was glad to help facilitate both a discussion about intersectionality on both a professional and personal level with the Salve community.

“As a white woman, the only oppression I face is being female, but when one is a woman and African American, [she has] so much more to overcome,” Sealy said. “When these social classifications intersect, it can produce such negative experiences that as a society, we all should be aware of.”